Invisible Citizens - Researching the Marginalising Effects of Ghana Card

Ramatu Issah, MPhil from the University of Ghana, joined the CERTIZENS research group in 2023. Her research focuses on the relationship between citizenship and marginalization. She explores the experiences of Zabarmas and Fulanis in obtaining identification cards (‘Ghana Card’) and their perceptions of identity, citizenship and belonging. Ramatu reflects in a very personal way on how her case study relates to her own past experiences and how interview partners navigate injustices caused by the implementation of Ghana’s vision of a nation-wide identity system.

INVISIBLE CITIZENS

by Ramatu Issah

As a Fulani and Muslim woman growing up in Ghana, I have encountered substantial discrimination and marginalization within various social and educational contexts. During my high school years in the Ashanti Region, a farmer-herder conflict in Agogo was unfolding, accompanied by extensive negative media coverage that often targeted the Fulani community. At the same time, a Kumawood movie titled “Fulani Landguard” was released, depicting Fulanis in a highly derogatory manner, as mischievous, violent individuals.

In another case, a history lesson at school on the spread of Islam in West Africa became a platform for discrimination. The teacher, while discussing the role of Fulani nomads in the spread of Islam, shifted focus from the historical content to make a personal attack, stating, "Ramatu's people are now killing us here in Ghana." The teacher further questioned the class about the perceived troublesome nature and non-Ghanaian identity of the Fulani community. This incident profoundly impacted my educational experience, leading me to withdraw from the history class for the remainder of my time at the school.

Moreover, this pattern of discrimination persisted into my undergraduate studies at the University of Ghana. In a course on the archaeology of West Africa, a lecturer explicitly linked rape cases in Ghana to the Fulani community, reinforcing the stereotype of Fulanis as non-Ghanaians and perpetrators of violence. This prompted me to challenge the lecturer’s ethnocentric assertions publicly. However, this trauma is something that lingers for a long time. Working on issues of citizenship is a privilege, and I approach this work as both a researcher and an activist.

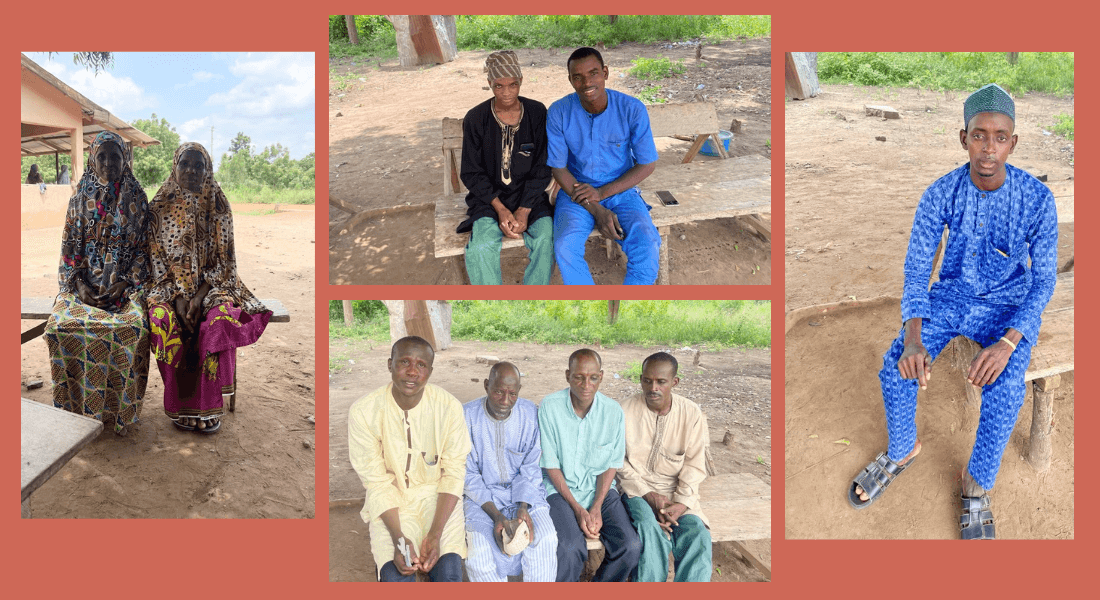

While collecting data in the field, I realized how privileged I am despite the discrimination I have faced. Speaking with respondents in the North Tongu district who have had no access to education made me appreciate the advantages I have as an educated Fulani person. In many conversations, the Fulani and Zabarma respondents shared their experiences of discrimination and marginalization. These experiences ranged from being removed from commercial vehicles for dressing in a way deemed "unacceptable", to altering their identities on documents in order to fit in. Despite meeting the constitutional criteria for citizenship, bureaucrats, police, and immigration officials often use unlawful means to deny them their rights, sometimes demanding bribes and ignoring legal rights and protections.

This marginalization impacts every aspect of their lives, from economic activities to health. The Ghana Card, required for SIM and bank registrations, has become a critical barrier. Without it, many cannot save money or access health insurance benefits, as the card is now linked to the health insurance system. Reflecting on the data I obtained, I must judge that the framework for citizenship identification in Ghana has failed: rather than facilitating improvements in the lives of all citizens as it claims to do, it complicates and obstructs the lives of particular groups of citizens. The inconsistencies and impunities in the system allow bureaucratic officials to exploit people, demanding payments for essential documents to which they are constitutionally entitled.

Although all respondents in my study possess voter ID cards, they struggle to obtain passports, and Ghana Cards. Some respondents with one parent from ethnic groups considered as indigenous like Ewe, Ada, or Akan, have had to align themselves with these identities to obtain citizenship more easily, as opposed to their Fulani and Zabarma identities, which are more challenging to validate. My field experience pushes me to raise a critical question: whose citizenship is real citizenship in Ghana?