Master Thesis Presentation: Ramatu Issah

Ramatu Issah, CERTIZENS member and recent master's graduate at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, presents her thesis on 'Citizenship and Marginalization: A Comparative Analysis of the Experiences of Fulani and Zabarma Groups in the North Tongu District of the Volta Region of Ghana'.

Citizenship and Marginalization: A Comparative Analysis of the Experiences of Fulani and Zabarma Groups in the North Tongu District of the Volta Region of Ghana

What is your research question and where and how did you go about doing your research?

My thesis research was conducted in the North Tongu District in the Volta Region of Ghana. The Fulani and Zabarma groups form part of the largest migrant populations in this district. They have a long history of migration, primarily from the Sahelian regions, including Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, with documented evidence of their presence in Ghana dating back to both the precolonial and colonial eras. Despite this, they continue to face challenges in being recognized as legitimate citizens. My research explores the following question: ‘In what ways have historical migration patterns and the politics of exclusion shaped the identity and belonging of Fulani and Zabarma migrant groups in Ghana, and how do these dynamics influence their access to national identification, state services, and relationships with the ‘indigenous’ population?’

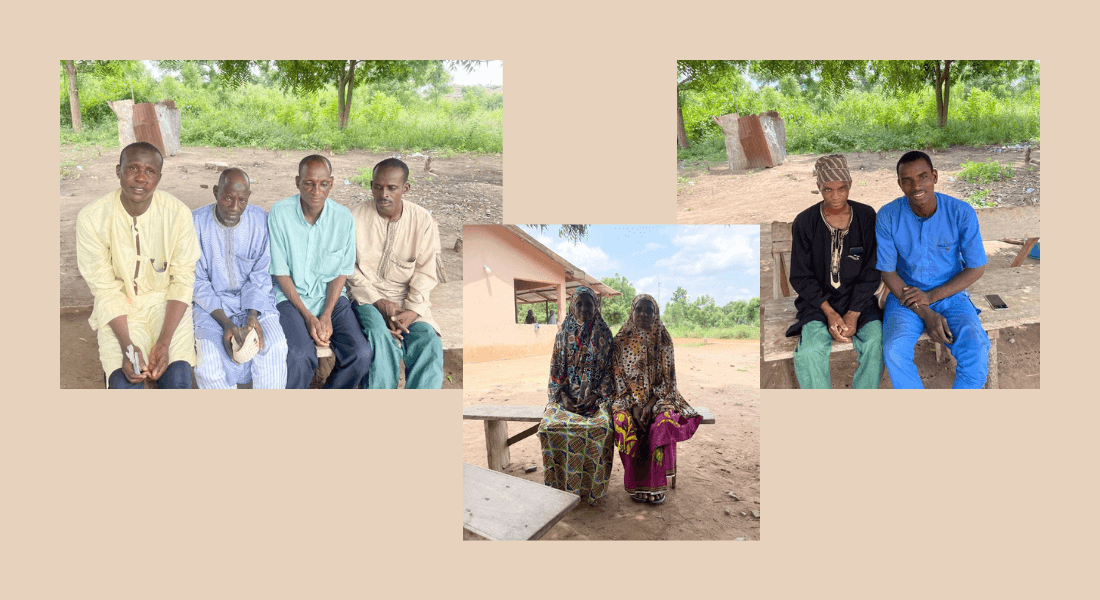

The study employed a qualitative approach, utilizing interviews and focus group discussions, supplemented by secondary data analysis from pre-existing research. A total of twenty-nine respondents, both male and female, were drawn from the selected Fulani and Zabarma communities to provide insights into their experiences. The majority of research participants were second-, third-, or fourth-generation migrants, with some having family members who served in the military.

What were your key findings and why do they matter?

My findings reveal that many people among these communities are excluded based on arbitrary factors, creating feelings of alienation. It shows that bureaucrats often deny people identification documents based on their appearance, accent or surnames, leading some individuals to adopt new names to try and fit in. Additionally, it reveals that the framework of national identity often overlooks people’s historical connections and integration within their communities, which can lead to community tensions. Again, the findings show how the citizenship registration process has strained relationships between migrant communities and ‘indigenous’ people, with bureaucrats increasingly relying on locals to challenge apparent migrants' citizenship status. This is also mirrored in wider society, where negative media coverage of certain so-called migrant groups like Fulanis and Zabarmas has influenced how they are perceived more generally.

Overall, the findings reveal that urban-based migrants found it easier to acquire identification documents such as the Ghana Card, voter’s card, birth certificate, and passport compared to rural-based migrants, highlighting the role of education and social status in accessing identity documents. In terms of types of ID documents, voter ID cards were more easily accessible compared to other forms of official identification.

These findings expose the state’s (informal) tendency to rely on stereotypes to recognize legitimate citizenship rather than recognizing the historical ties and community integration of second-, third- or fourth-generation migrants. Exclusionary practices create barriers to essential services, limit civic participation, and strain relationships between so-called migrant and ‘indigenous’ communities. A more inclusive system is needed to reflect West Africa’s traditions of migration and cultural diversity, ensuring fairness and inclusion.

Why is your research relevant for the broader discussion on IDs and citizenship in Africa?

The study engages with the significance of state-citizen identification registration processes and their implications for wider citizen inclusion and exclusion. It problematises the notion of citizenship rooted in an exclusionary politics of belonging by tracing the histories of migration of marginalized groups in Ghana and their integration into local ‘indigenous’ communities.

Additionally, it examines the impact of economic and spatial factors on the experiences of ethnic minorities by contrasting the fortunes of those integrated into urban areas and those within rural settings. It also examines the difference in experiences of male and female long-term migrants. Finally, the study unpacks the combined influence of cultural factors, education, language, status, and physical appearance on the construction of national ideas of legitimate citizenship and practices of exclusion from citizen rights. By focusing on the interactions between national citizen registration conducted by agents of the state, and processes of integration into communities, the research contributes to the existing literature on citizenship and the lived experiences of migrant communities with long histories of migration in Ghana.

The study also has important policy implications, offering insights for a deeper understanding of the intersection of migration, identity, identification, and citizenship, locating this within the broader history of regional economy and historical movements of people in West Africa. This can help to inform a more reflective approach to inclusive citizenship laws and biometric identification processes. This in turn could also ensure that these systems are more accessible to all citizens, regardless of their ethnic background, and are grounded in the realities of people’s lived experience, fostering social justice and equal access to rights and services.

To access the full thesis, please contact the author via iss.ramat@gmail.com.