Privacy Summer School Revisited ‘Either you get dizzy, or you enjoy the roller coaster ride’

A group of students from all over the world was at the frontline of humanities research when they participated in an ambitious summer course at Centre for Privacy Studies. The course required a pioneer mentality of all people involved, as the academic field is still largely unexplored: What is it made of, this so-called privacy, that we are trying to defend against Facebook, Google and governments? Usually, it is quite easy to guess what people are doing behind the glass walls of the classrooms in the west end of South Campus at University of Copenhagen. PowerPoints and paragraphs reveal the law students. Notepads with Greek letters give the theology students away. However, for two weeks this August, even the cleverest among amateur detectives would have had trouble de-coding what was taught behind the glass in classroom 6B.0.22.

Usually, it is quite easy to guess what people are doing behind the glass walls of the classrooms in the west end of South Campus at University of Copenhagen. PowerPoints and paragraphs reveal the law students. Notepads with Greek letters give the theology students away. However, for two weeks this August, even the cleverest among amateur detectives would have had trouble de-coding what was taught behind the glass in classroom 6B.0.22.

A rather diverse group of students was gathered. Their home universities included Yale, Tokyo, Sydney and ITU, their home countries China, Germany, Australia, Japan and Singapore. Their main fields of study were as varied as pedagogy, philosophy, IT and social sciences. To top the complexity of it all, their teachers were researchers in areas such as anthropology, architecture, church history, social science, philosophy, law and public health.

They were all here to be part of the summer school ’Privacy challenged in past, present and future: a multi-disciplinary approach’ offered by Centre for Privacy Studies (PRIVACY) at University of Copenhagen. Here, researchers and students worked together to dissect and analyse the multi-faceted concept of privacy.

‘Privacy is high on the political agenda in many contexts, and everybody agrees that privacy is important. However, we do not have an authoritative definition of what privacy actually is. We are only just starting to build a systematic understanding of the different roles privacy plays in our culture and humanity,’ says Professor Mette Birkedal Bruun. She is director at the Centre for Privacy Studies and initiator of the new summer school.

The professor’s own background is in Church History, and the academic approach at both the Centre and the summer school is the need to look at history to understand what privacy is about today.

‘Privacy and the private is understood and valued very differently across time and place. Historical research makes it evident that all of these different concepts of privacy are contextual and embedded in value systems. History can help us see these value systems and even cast some light on the value systems we are embedded in today, which are much more difficult for us to see,’ says Mette Birkedal Bruun.

No basic textbook to follow

With privacy being a rather new subject of academic interest, the studies have placed high demands on both teachers and students. The research centre is not even two years old yet and the research is highly interdisciplinary, bringing together knowledge from history, theology, law, philosophy, sociology, architecture, art history and much more.

‘We have demanded a lot of our students and of ourselves. It can feel as a forced expansion of the horizon when you are constantly connecting the various perspectives from different disciplines. I told the students from the beginning that there were two options: Either you get dizzy because this feels too weird, wild, and big, or you enjoy the roller coaster ride and throw yourself into it. And they were so incredibly good at embracing the roller coaster ride,’ Mette Birkedal Bruun laughs.

Each day on the course they explored a new theme, both historically and from a contemporary perspective, such as “privacy and surveillance” or “privacy and the body”. This meant that on Thursday the students had to familiarise themselves with DNA registers and health laws, Friday with some of the key thinkers of social sciences, and on Monday with the worldview of Christianity and existential philosophy. By then they were not even halfway through the course.

In the midst of it all, Professor Mette Birkedal Bruun was in charge of maintaining the overview and connection to the common thread.

‘I have been at the edge of – or outside – my scientific comfort zone half of the time during these 14 days. It has been a challenge, but also a great gift to me as a researcher,’ she says.

Fortunately, when it came to the common thread of the course, Mette Birkedal Bruun was able to offer the theories and models that the Centre uses in their research. They focus on highlighting the thresholds and limits for the spheres of privacy, as the concept of privacy is often identified when its limits are infringed upon.

‘We have been very fond of the zone model we have developed here at PRIVACY. It is practical and does not require that you have read a lot of theoretical works. It was great to see the students using the model in class. One of the students said that they really felt they were part of the research now. I felt that too,’ says Mette Birkedal Bruun.

Students make researchers smarter

The fact that the students and the teaching situation itself contribute to the research cannot be stressed enough, the Professor finds.

‘I really think that this summer school has brought our research a giant step forward. Some of our insights were sharpened and we dared ask some of the questions that we, as researchers, sometimes are too cautious to ask because we want to be on completely steady ground before doing so. The course has been an academically horizon-expanding experience for us all. In particular, it was a huge benefit that the students came with very different cultural and academic backgrounds.’

Some of the students came from Asia, and consequently the differences between the Asian and the Western perceptions of privacy became an important theme throughout the course.

‘In Asia and Africa many perceive privacy as a mainly western concept, and it became evident how much the concept of privacy is embedded in western culture. We knew that to some extent already, but the differences can really be distinct when teaching in a multicultural classroom,’ says Mette Birkedal Bruun.

Sinister living rooms?

She experienced an expression of the different cultural backgrounds among the students when the class went on an excursion to the art museum, The Hirschsprung Collection. When the Danish students saw the artist Vilhelm Hammershøi’s iconic paintings of Nordic empty living rooms and people contemplating in privacy, they expressed enthusiasm about the beautiful paintings. The students from other cultures, however, all perceived the paintings as sinister. ‘This is not privacy, this is loneliness,’ they said.

‘Of course this is not a scientific insight, but it is a good starting point to ask the good questions: What is it we value, when we value privacy so highly? And is it a completely different concept, when other cultures have a concept of privacy that they value? It is very difficult to legislate about privacy across countries if all have different perceptions of it. We have a task before us defining and translating the different components that the concept of privacy contains across cultures,’ Mette Birkedal Bruun says.

What do the students think?

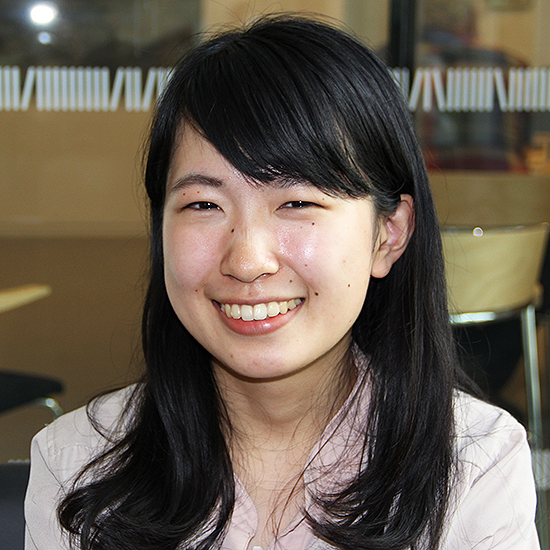

Aya Sudo from Japan

Studies humanities, general arts at University of Tokyo.

The course is great, but also challenging because the teaching style is so different here than to what I’m used to. It is very interesting with so many different nationalities and cultural backgrounds in one classroom.

Privacy is very much a western notion, and a rather new concept in Japan that many people do not really understand yet. In Japan the concept is just relating to security and is a very new issue that we have only recently started to discuss.

In Western countries the concept has a long history in relation to Christianity, so it’s very interesting to come here and learn about it.

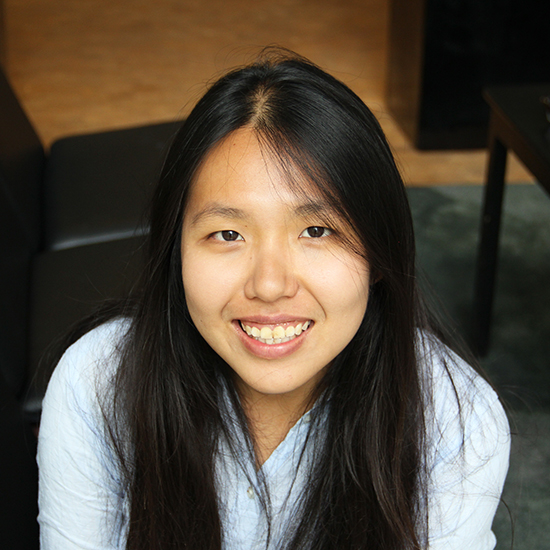

Yu Ching Tan from Singapore

Studies public policy at University of Tokyo.

The course is much better than expected. It has been a long time since I have had this experience of having a real revelation at university. So many aspects of this course are brand new to me.

The course appealed to me because I want to work in the tech sector where privacy has increasing importance, but I can see that there is often a somewhat limited understanding of privacy.

The cross-country comparisons add so much to the teaching of this course. Danes have a much stronger sense of privacy than we do. You are very protective of it.”