Spot on PRIVACY scholars: Asta Mønsted and Natalie Körner

Archaeologist Asta Mønsted and architectural historian Natalie Körner are currently collaborating on a research project titled Privacy in the Greenlandic Inuit House of the 19th Century. Together, they explore the complex relationship between architecture, material culture, and social change among the Greenlandic Inuit. Their focus lies on the vernacular, shared winter house, examining how its spatial organization was not only designed to provide shelter, but also gave rise to a specific experience and understanding of privacy. This deep and consistent sense of privacy, they argue, was gradually transformed with the introduction of new European building materials and architectural elements, starting from the middle of the century. In this interview, Asta and Natalie explain about the insights they have gained so far, and how their respective disciplines complement and shape the project.

Can you begin by describing what houses you are looking at, and how they were built and organised?

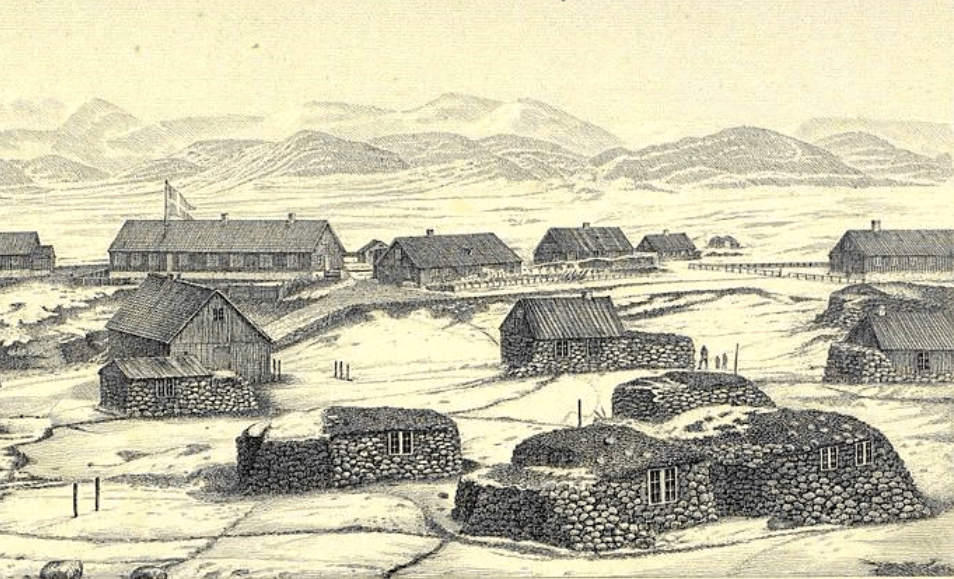

Asta: We are working with communal winter houses from the 1800s, especially the large, rectangular houses around Disko Bay and further down along the West Greenland. They could sometimes hold up to sixty people and were built from stone and turf, with a low entrance tunnel leading to a raised sleeping platform where the heat gathered. Each family had a compartment, separated by skin or fur hangings, and a soapstone lamp for heating and cooking. There were also side platforms for unmarried men, widowers, or visitors. So the architecture reflected social ties and status.

Natalie: What was really interesting for us was looking at the seasonal transitions. In the summer, families lived in tents—nuclear units with parents, children, maybe a grandparent. Then in the winter, they moved into these large houses, often based on hunting relationships. Families who hunted together would live together, and each nuclear unit got a compartment on the sleeping platform, separated by hangings. This structure mirrored the summer tents and shows a consistent way of organising space and privacy across seasons.

How do you investigate privacy in these houses, and what have you learned about how it was experienced?

Asta: We chose to look at the skin partitions, the soapstone lamp, and the entrance tunnel because we thought these might be boundaries or thresholds—like Mette Birkedal Bruun calls them—between public and private space. Examining these materials helped us understand the very concrete, human experience of privacy inside the houses. Natalie noticed the connection between the summer tent, with skins on the outside surrounding the nuclear family, and how that idea was basically copy-pasted into the family compartments in the winter house.

Natalie: What we found was that privacy was created through small social gestures and negotiation. For example, drawing a skin or fur curtain meant ‘now we want privacy,’ but it did not mean nobody could hear or maybe even see you. Instead, people got privacy simply because others granted it. This kind of negotiation within the community is what we see in these houses. And this also reflects how we approach privacy theoretically—as something universal, but also fluid and culturally specific, always negotiated in practice rather than fixed.

What motivated the Danish administration’s interventions in housing, and how did the new building materials affect privacy?

Asta: The communal structure did not fit with the Danish administration’s interests. They wanted each hunter to sell more seal skins, which could be hunted individually—unlike whales, where you needed several hunters working together. By splitting up families and housing, hunters could cover larger areas and deliver more seal skins.

Natalie: The administration also wanted to westernize the homes—move away from the communal, which from a Western perspective was quite unfamiliar. They wanted to clean up the houses, bring in more light, and introduce modern heating technologies. So it was not just about productivity—it was also about reorganizing the space and the social life inside it.

Asta: Before the new materials were introduced, privacy was more negotiated and flexible. In the communal house, the hangers were not there all the time—you put them up when you were going to sleep, or if you wanted private space with your husband, for example. In one oral story, the mother-in-law is peeping in to make sure that there will be grandchildren, so in that way the hangers signalled privacy, but it could be disrupted. That was possible because the materials allowed it. As walls were introduced, divisions became more non-negotiable, changing how the private space was experienced.

Natalie: Yes, privacy shifted from something gestural and relational within a larger community, to something tied to spatial isolation in single-family houses, where the boundaries were much more rigid. It became less about gestures and more about actual spatial constraints. However, what I find fascinating about privacy is that it is fundamentally reciprocal—you can draw boundaries, but someone else has to also grant and respect them. While this may have been more obvious with the more fluid markers, the new spatial conditions still relied on this reciprocity. Glass windows allowed for unfiltered views, and wooden doors made the link between inside and outside more immediate. This engendered new ways of negotiating boundaries.

What kinds of sources do you use, and how do your two fields—architecture and archaeology—work together?

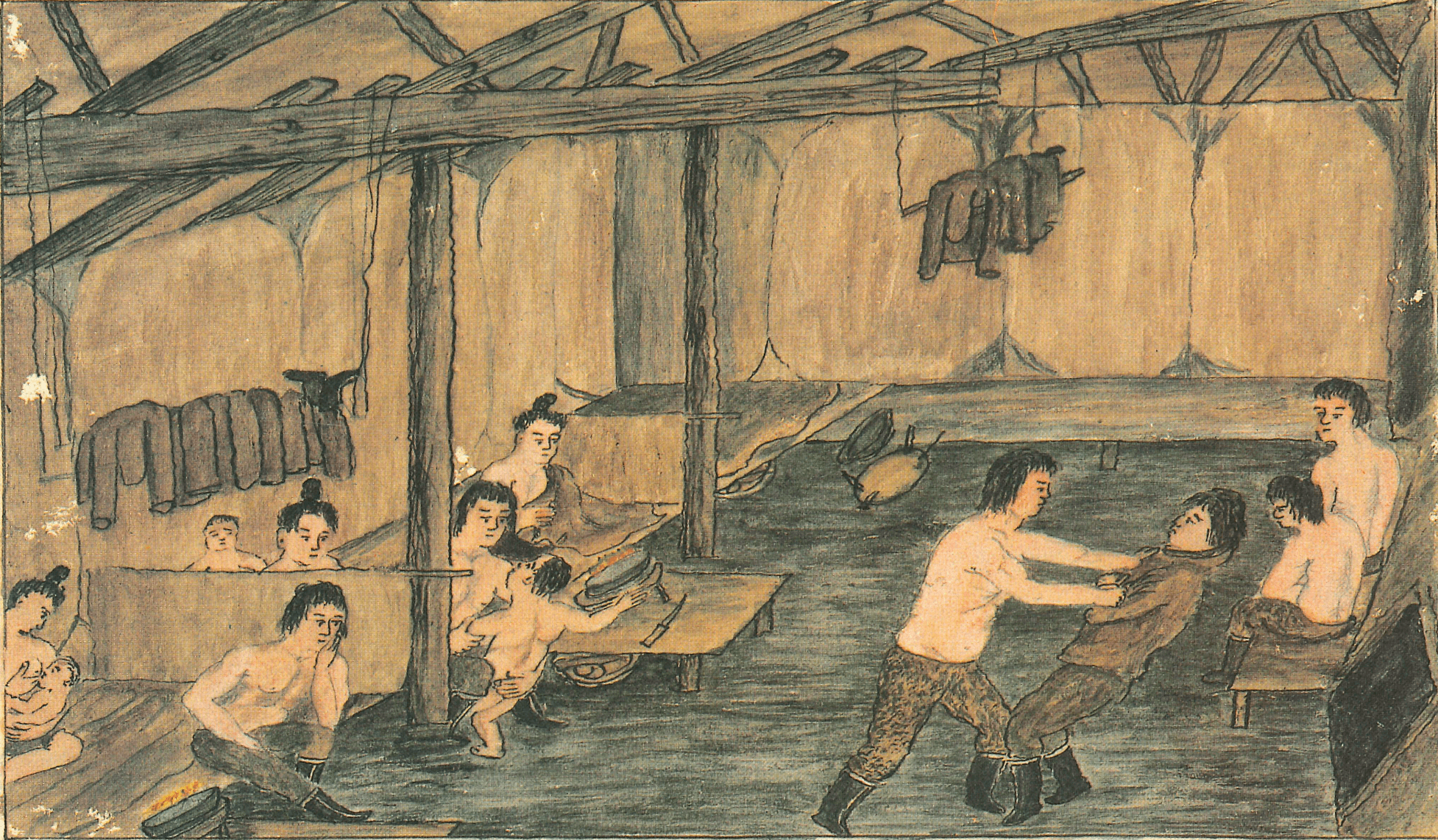

Asta: We work with different types of sources: archaeological remains, historical accounts—often outsider perspectives—and ethnology sources. Oral history gives us insider stories, usually through myths and legends. For example, in the story I mentioned earlier, where a young woman wants to be intimate with her husband, we can use that moment to understand how people lived and drew boundaries—although the genre is not empirically descriptive. We also have Aron of Kangeq’s sketches, which are valuable because they are contemporary and based on his own experience of being inside those houses.

Natalie: It has been really productive to combine so many different types of sources to investigate inhabitation from both an architectural and archaeological perspective. I have learned so much from Asta, especially about the Greenlandic context. What I really appreciate is the archaeological way of answering questions through objects—if there are no material indicators, then maybe it did not exist. That makes sense to me as an architect, even though I might be more speculative. But we both turn to material evidence and concrete things to imagine inhabitation. I embed the material into spatial practices, and Asta into the broader historical context.

Has anything surprised you in your research?

Asta: I am not sure it was a surprise, but I definitely had an aha moment when Natalie pointed out how the tent structure was carried into the communal house. I have looked at tents and winter houses for many years, but I had not thought about it that way. And we actually see it very concretely in Gustav Holm’s registration, where the same family members shift from separate compartments in winter to shared tents in summer. It says a lot about how privacy and space change with the seasons.

Natalie: What surprised me most was how many things came together in the 19th century to disrupt an optimised system. These houses were not meant to be permanent—they were built with local materials and meant to be partly dismantled and aired out after winter. But as colonies, churches, and communities settled, that way of living no longer worked. Additionally, the iron stoves did not allow for the same kind of gathering-around as the gentler soapstone lamps. That is the thing with vernacular architecture—if you alter one part, the whole system needs to change.