and the Critique of Systematic Philosophy

KIERKEGAARD’S COPENHAGEN

Private Eye and Street Preacher

Some of my fellow countrymen no doubt think that Copenhagen is a boring little town. But I think (…) it’s the greatest place I could ask for. Big enough to be a fair-sized city, small enough that there isn’t a price tag on people. (Brev 36. Source: SKS.dk)

This warm description of Kierkegaard’s Copenhagen is from Stages on Life’s Way, published in 1845, when the city had 126,787 inhabitants. Kierkegaard knew the city like the back of his hand, and maybe even better than that.

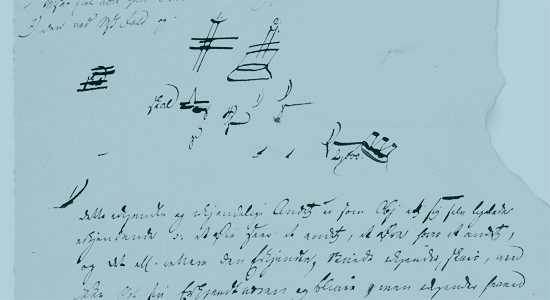

Populated with the finest objects of study of virtually every kind—crazy and genius, plebian and aristocratic, impoverished and wealthy—Copenhagen was a pulsating psychological laboratory for Kierkegaard. He returned home to his writing desk enriched with situation and mood, which he retained in his notebooks.

Private Eye

He wore boots of special design with inlaid cork, which was no doubt added to help protect his weak legs. In addition, these boots must have been completely practical for the brilliant “private eye” who sneaked silently through his city. It’s hardly a coincidence that he called the pseudonymous author of The Concept of Anxiety Vigilius Haufniensis: “the vigilant Copenhagener.” He loved to disappear into the crowd and leave his cares behind. He wrote this to his sister-in-law Henriette in 1847:

Above all, do not lose the desire to walk. Every day I walk myself into a state of well-being and walk away from every illness; I have walked myself into my best thoughts and I know of no thought so burdensome that one cannot walk away from it. (...) Thus, if one just keeps on walking, everything will be all right. (Brev 36. Source: SKS.dk)

The Street Preacher

Kierkegaard liked to take his walking companions by the arm, which gave the walk a kind of intimacy. Just as he brought the lights and sounds of the city to books, he also practiced his understanding of existence out in the city. He was a Danish street preacher before the concept existed, a practitioner of democracy before democracy was established in Denmark. But it wasn’t easy to keep in step with him. Because of his physical awkwardness and his lively gait, his walking companions risked either being pushed up against the buildings and into the stairwells on the one side, or being pushed into the open gutters on the other side. He was a spirit out for a walk, a dialectical spirit—and thus the zig-zag on the streets. The fact that he gesticulated with a walking cane and suddenly crossed the street to avoid direct sunlight made it even more difficult to avoid detection when accompanying the genius on his walks.